Lethal vs. Non-Lethal Control

Removal of coyotes by lethal means—though it may be necessary for some problem individuals—is not effective for population control. Lethal methods like hunting, trapping or poisoning—especially in neighborhoods—are generally more dangerous to pets and the community than to the problem coyotes. Eliminating an entire group of coyotes, rather than solving the problem, simply creates a vacuum that other coyotes will fill. Moreover, if a resident pack is removed, it will likely be replaced by transient coyotes, who are often even less desirable. Unless a new pack is formed and a territory defended, the area could soon be overrun by transients, who may become problem animals that have to be removed. Relocation is not an option because it is illegal in Rhode Island.

While eliminating problem individuals is sometimes in order as a short-term fix, there is a non-lethal management tool that offers more of a long-term solution: controlling the coyote food supply. Unlike deer and most other wildlife, coyotes have an intrinsic ability to control their own numbers. Their reproductive rate is regulated by the amount of food available. If coyotes sense less food, they reduce their litter sizes and numbers of breeding females. The reverse is also true: more food, more puppies. So, if coyote numbers are reduced by lethal means, the remaining coyotes will have more to eat and will respond accordingly by increasing reproduction.

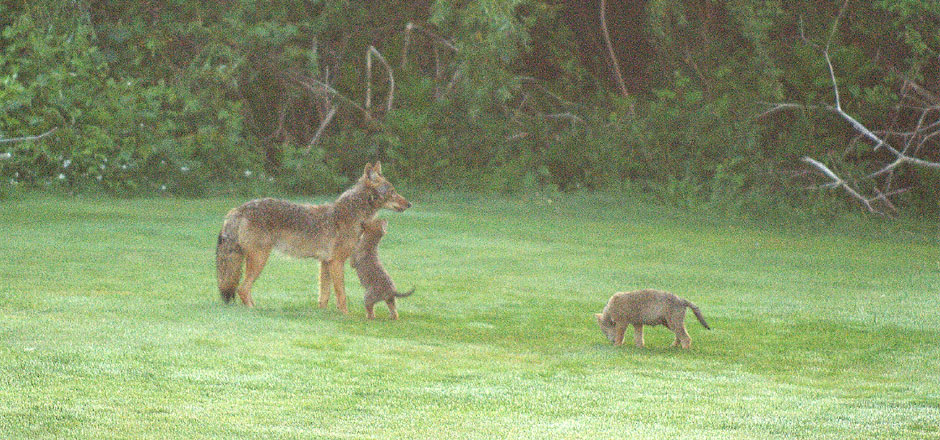

The Narragansett Bay Coyote Study has determined that large amounts of food are being provided, usually unintentionally, to coyotes in our region by people. Our coyotes have responded to the “easy pickin’s” in two ways: 1) by increasing their birthrate (more food, more puppies) and, where they begin to connect food with people, 2) by becoming habituated—losing their natural fear of humans. Coyotes are opportunistic and smart: any easy pickin’s will train them to return to look for more food. If those easy pickin’s are coming from people, the coyotes learn to stare at people instead of running, or even to approach, to see if they are going to get a handout. Food is the root of the “coyote problem.”

As easy as the “coyote problem” is to create—just add food—it is as easy to solve. All we have to do decide there’ll be no more easy pickin’s for coyotes and we reverse the process. We know why: less food=fewer pups. Coyote numbers will decrease to a level sustained by natural foods, and, since they are not being fed by people, coyote habituation problems will disappear.

Best Management Practices

Recognizing the role of food supply in controlling coyote populations, the Narragansett Bay Coyote Study has developed a set of recommendations—Best Management Practices for Coexistence with Coyotes on Aquidneck and Conanicut Islands—that address such issues as:

- Road killed deer and other animals

- Link between deer abundance and coyote population numbers

- Farm livestock carcasses

- Intentional and unintentional feeding by residents

- The feeding of free-roaming, outdoor, and feral cats

- Policies for normal vs. problem coyotes

- How to best reduce the number of coyote-related complaints

All four towns on Aquidneck and Conanicut Islands have adopted some or all of these recommendations.

Local No-Feeding Ordinances

While Rhode Island and other states have laws on the books that prohibit the feeding of wildlife, local ordinances can be a valuable management tool for communities with active coyote populations.

All four towns on Aquidneck and Conanicut Islands—Middletown, Portsmouth, Newport and Jamestown—have adopted a “no-feeding ordinance” recommended by the Narragansett Bay Coyote Study. The ordinance prohibits not only the intentional feeding of coyotes and other wildlife, but also the leaving of food attractants of any kind in places where it is accessible to them. As the study’s lead scientist points out, “Since the problem coyotes that are created by feeding do not recognize town boundaries, the towns’ ordinances are mutually supporting and should decrease coyote traffic in neighborhoods and interactions between people, their pets, and coyotes.”

Forensic Tracking

Using GPS data from collared coyotes, the Narragansett Bay Coyote Study was able to identify their major food sources and prepared a Summary Report on the Results of the NBCS Forensic Tracking Program for submission to the municipalities of Aquidneck Island and Jamestown. It reveals all the food resources provided by residents to coyotes and makes some recommendations for action.

NEW: Coyote Management Toolkit for Rhode Island Municipalities

Drawing on the above resources, we have compiled a “Coyote Management Toolkit for Rhode Island Municipalities.” A PDF is available on request from coyote@theconservationagency.org.

“Safe Cycle” Method for Roadkill and Livestock Carcass Disposal

If not properly disposed of, roadkill and livestock carcasses can provide a major source of food subsidies for coyotes. There are well over 1,000 deer killed on Rhode Island’s roads every year, 25-30 of which can be found on Aquidneck Island and the same on Conanicut Island. Some are buried or trucked to landfills, while others are simply moved to the side of the road where coyotes can find and feed on them.

Coyotes also feed on the carcasses of farm animals, which often die in the winter when burial is difficult and when coyotes are in breeding season. Abundant food at this time contributes to coyote fitness, which in turn leads to increased reproductive output.

Unburied livestock carcasses create a secondary problem: coyotes that discover them will develop a taste for that particular type of livestock. In other words, coyotes that learn to eat dead sheep will generally begin to go after live sheep. Farmers need to thoroughly dispose of carcasses, out of reach of coyotes, to insure their farms are not a training ground for livestock predators.

An alternative to burial is a process we have dubbed “Safe Cycle” that uses an alkaline hydrolysis digester to dissolve carcasses, destroy pathogens and create fertilizer. A pilot carcass recycling study on Aquidneck Island in 2011 showed that 2300 pounds of roadkilled deer generated in one average week could be converted to liquid fertilizer in 18-24 hours. Discussions are underway between the RI Department of Environmental Management and the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, which funded the study, regarding the funding and operation of one or more of these units.

Photo credit: ©Irene Pasyanos, Middletown RI